And the race is on!

The scene starts upon a great river—a looming emperor sitting above it all. Animals make their way to the starting line, all fighting for the top twelve spots.

Now, this not only makes an excellent premise for an animal kingdom Great Race spin-off reality TV show, but it is also the basis of the Chinese Zodiac. The top twelve victors of the river race: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig were formed into the now recognizable representatives of the Chinese lunisolar calendar.

What is Chinese New Year?

The Lunar New Year, unsurprisingly, falls on the first day of the lunar calendar. In terms of the Gregorian year, it usually finds itself on the first new moon between January 21st and February 20th.

Chinese New Year is far from the only holiday celebrated on the Lunar New Year. Ethnic groups all across Asia and the Middle East celebrate the new year based on a lunisolar calendar, though not necessarily on the same day. In Vietnam, Tết Nguyên Đán (Festival of the First Day) is typically regarded as the most important celebration in the whole year. For Koreans around the globe, Seollal (Year of Age) is the perfect time to don traditional hanbok, eat tteokguk (soup with rice cakes), and play folk games like Yut Nori.

In China, celebrations for the new year typically last fifteen days, collectively known as the Spring Festival. One wouldn’t need to look too closely to find evidence of the festivities. Red couplets strung up on household doors denote wishes of wealth, longevity, and fortune for the upcoming year. It is also a time to profit off of your closest relationships! Red envelopes filled with money are often gifted during the festival, which in truth, are not only significant for the cash inside, but for their blessings of prosperity. A good rule of thumb during the Chinese New Year is to never stray too far from the stage. To ward off evil spirits, leaping lion dancers defy gravity to the beat of thrumming battle drums and snapping firecrackers. Try to tear yourself away from the mesmerizing dragon dance as you wonder what is more impressive—the sheer force of such a beast? Or the single-minded unification of ten people to put on a show?

The Year of the Dragon

This year is an especially important celebration. Even amongst the rest of the zodiac, the year of the dragon marks a huge turning point for Chinese culture. Considered particularly auspicious, many parents even try to time births in dragon years. Luckily, San Marcos has the fortune of having our very own on campus. Born in June of 1988, Trevor Oftedal, World History teacher and rugby enthusiast, was gracious enough to go into detail about his thirty-five years of dragon experience.

“I always just knew that there was something different about me. Something special. It must’ve been the dragon inside,” said Mr. Oftedal.

Dragons sport a wide range of admirable qualities. Tenacity, natural leadership, and quite possibly a booming voice that can be heard five hallways down. To all the future dragons being born in 2024, he has a few words of wisdom.

“Do as the dragon do. Do as the dragon would do. Do do dragon do. Dragon doo doo,” said Mr. Oftedal. The wisdom of the dragon is evident.

Celebrating in the States

While the event itself has a long ancient history, it has taken on a whole new meaning for Chinese Americans. The first large movement of Chinese immigrants into the U.S. occurred in the 19th century. Not only a dragon, Trevor Oftedal was also the most available history teacher and was able to provide some context.

“There was social and economic upheaval in China. One of the places that work was readily available was the growing United States, particularly as the United States was putting in railroads to connect coast to coast. The Chinese were instrumental in building the railroad systems,” said Mr. Oftedal.

During the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad, Chinese workers faced racial discrimination like work camp segregation and reduced wages. They were often forced to work the most dangerous jobs where deadly rockslides and explosions were frequent.

“One of the ones that always stuck out ot me was that in order to dynamite certain cliffs they would hang a rope down the edge of the cliff, a Chinese person would have to take the dynamite stick it into the mountain, light it, and climb up as fast as they could before it exploded,” said Mr. Oftedal.

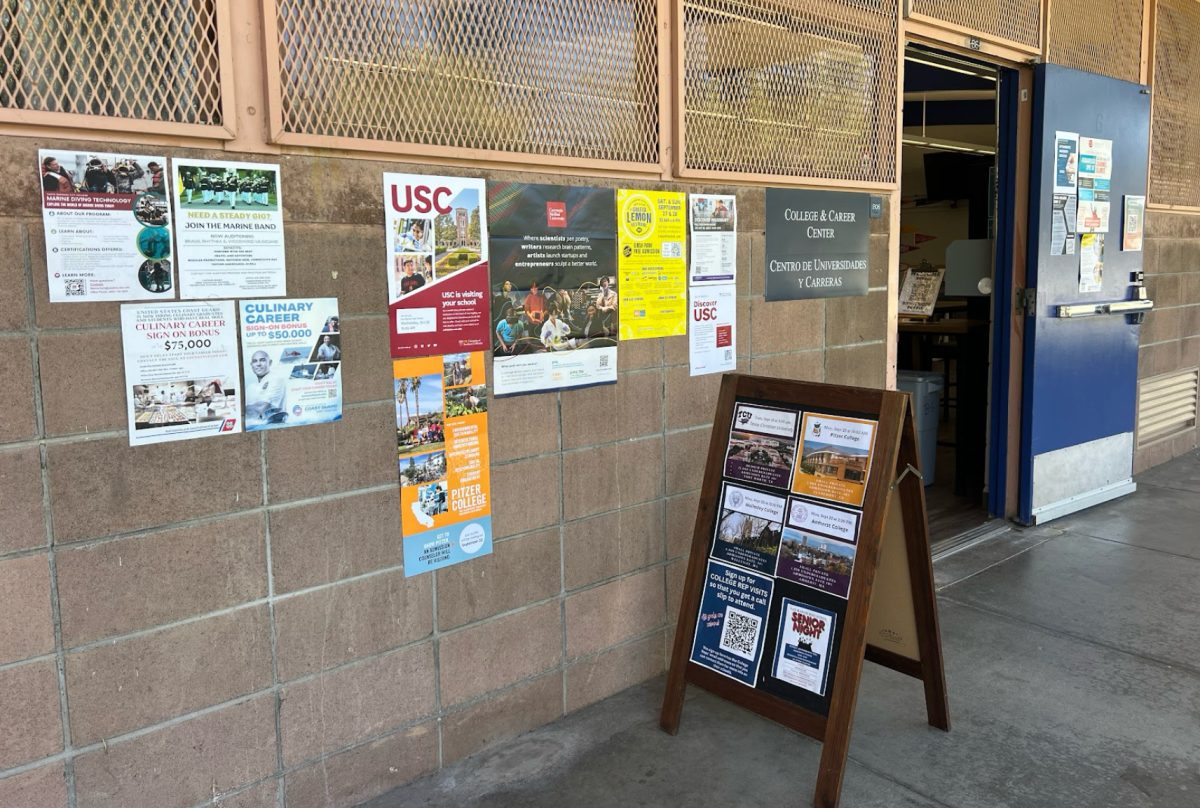

During this time, events like the Spring Festival served as a way to unite workers and preserve culture. In the 1860s, the first Chinese New Year parades started being held in San Francisco. Though strangely absent in American festivities, these parades were often subject to strict regulation and blockades. Despite the rampaging xenophobia, these celebrations have persisted, now becoming a time honored tradition, and symbol, all across the U.S. In a story of endurance, resiliency, and community, Chinese New Year is being kept alive in the States, and even in Santa Barbara.

Santa Barbara Festivities

Many revelers will tune into Central Chinese TV to watch the annual gala. The program features notable Chinese actors, comedians, singers, and dancers. But don’t fret, for those unwilling to find pirated reruns, and who prefer to stay a little closer to home, look no further than our very own Marjorie Luke Stage. On February 10th, it transformed into the only place in Santa Barbara to see classical dancing, tai chi, and Chinese choirs all on one stage. The non-profit Santa Barbara Chinese American Association and the Pacific Pearl Music Association of Thousand Oaks, partnered together to join these two communities in celebration.

The performance not only featured association members and local students, but also masters in their respective fields. Although it remains an instrument typically unrecognized in the mainstream, erhu player Yang Liu’s rendition of “The Galloping Warhorses” can only be described as “unforgettable”. However, the fan favorite of the night was clearly the adorable and charming Santa Barbara Chinese School’s children’s choir. In the show program, president of the SBCAA Neil Chu addresses the audience. “This is the first time we have had a large stage with such a large variety of performances. I am most grateful to the performers, volunteers and family for their invaluable talent, dedication, and service to our community,” said Chu.

The On Campus Perspective:

However, for many students, there is still a lack of recognition.

“I would really really love it if my family were able to celebrate it more because it definitely feels like losing a part of my culture,” said freshman Caroline Wang.

Most Chinese students on campus are second generation immigrants finding themselves walking the line between both identities. In an overwhelming American culture, it is common for many to become isolated from a Chinese community they feel unable to participate in. That bodes the question, does Chinese New Year serve as yet another separating factor?

“I think because I was surrounded by so many other people who were Chinese American and who didn’t grow up speaking perfect Mandarin, it was definitely more like a connecting experience,” said Wang, who still had fond memories of celebrations past.

“I was younger. Our other Chinese neighbors would come over to our house and we would eat hot pot. And hot pot’s delicious. I liked playing with the other kids and talking with them,” said Wang.

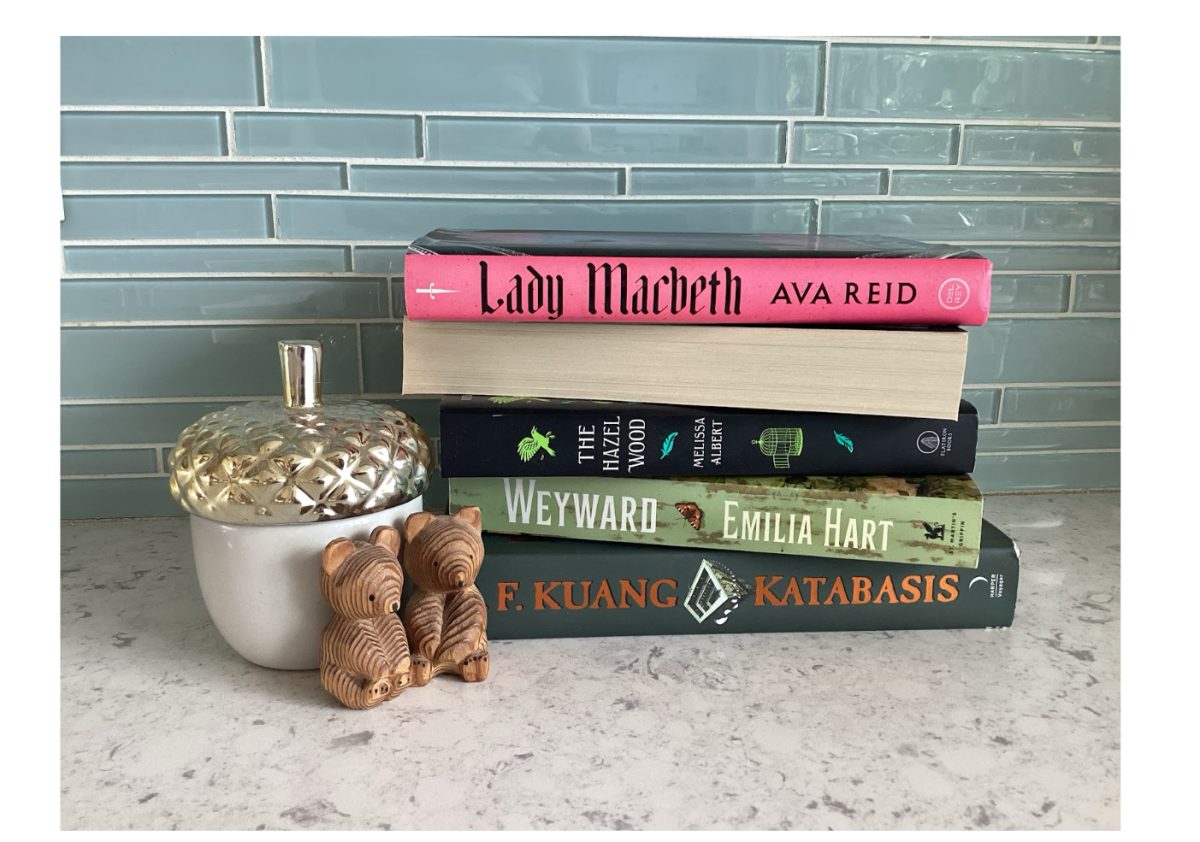

The most important part of the Spring Festival is the reunion dinner. Whether you find yourself in front of mountains of traditional jiaozi (dumplings) and changshou mian (longevity noodles) with family, or a reheatable TV dinner with friends, enjoy the people you welcome the year with.

The event has taken a somewhat mythological status itself. In the media and in American eyes, we find ourselves merely attracted to the reds and golds, to the painted opera faces—admittingly, this article even plays into that outward appearance.

But the truth is, at its core, Chinese New Year is a time for closeness, celebration, and fresh starts. It is a chance to find—or to even reconnect with community. While the first stories might have happened across great rivers, the best ones today happen across dinner tables.